Animal domestication as biotechnical emergence

The intention is to reinvest in the idea of domestication as varied systems of emergent relations. Ethnography will be used to mobilize an approach to humans and animals centred on processes, techniques and affects, allowing us to move beyond a narrow focus on species, whether in substantive states or in the dichotomy between control and autonomy. To this end, we will discuss situations like captivity, ferality and familiarization, but also encompassing humans, societies, artifacts and environments.

Guilherme Sá (UnB)

Coordinator

Graciela Froehlich (UnB)

Discussant

Free or à l´attache? Meanings and Techniques of restraints in dairy cow (Between France and Switzerland)

In the classic definition of animal domestication, which, although constantly criticized, continues to permeate many discussions, the issue of domination is a central element. It is not for coincidence that the best way to criticize and undo the bases of this very restrictive definition of domestication is, in part, to diminish the omnipotence of the human controlling agency and to giveback to the various actors their potentialities and capacities for actions and choices. These are movements that allowed domestication takes a path towards a sens of co-evolution, assembly, or sharing.

However, as Carole Ferret points out, this movement has certain limits and the asymmetries inherent to these relations and the restraints-type actions, fundamental at least in an immense part of the relationship with animals, should not be cover up in domestic processes. My proposal in this paper, based on Ferret's “anthropology of action” proposal, is precisely to analyze the techniques of restraints (in terms of space and time) in an ethnographic example where no one would doubt that this is a “domestic relationship” whatever the definition: dairy cows in France and Switzerland. The intention is not to once again posit domination as the defining feature of domestication, but to look at the technological choices at play in negotiations, orientations, or limitations for the other to do or not to do certain actions in this assemblage (the systeme domesticatoire centered on milk production). The technological choices and transformations, the mediation by technical objects, present in these moments of anthropo-zoo-genesis (Despret) that organize the possibilities of movements and the choices of animals and men in their actions, allow us to observe the complexity of these assemblages and multispecies socialities, and to bring out restraints not as the domination of the classical definition, but as an important moment in the construction of a common world between breeders and animals.

Creating water: domestication and emergence of life forms in fish farming

Fish husbandry as food production has been growing fast, including in Brazil. As a significant frontier of animal protein production, fish farming represents a vast contemporary domestication phenomenon with diverse formats and scales, allowing one to rethink the assumptions and paradoxes surrounding this crucial notion to understand the relationship between humans, animals, and plants. Without denying the centrality of human interest, it is necessary to assume the limitation of strict ideas of dominance, control, and proximity, paying attention to other agencies and even to phenomena that point to mutual influences, including those beyond direct interaction between humans and fish, including space, which is the domus where this process takes place. From two ethnographies (on the reconfigurations involved in the recent spread of fish farming of native Brazilian species), we will focus on the elementary process of "creating water". This activity involves generating and maintaining the physical and chemical properties of an aquatic environment to be favorable to the connection between certain vital processes of different beings. At the same time that it characterizes a captivity enclosure, the creation of water mobilizes skills, values, technical objects, and operations that transform, prevent, converge and make several processes between fish and humans (but also predators, microorganisms etc) compatible. The creation of water establishes resonances between the fish's metabolic dynamics and other processes, such as the networks for obtaining food and medicines and those for consumption or production outflow. Therefore, it is convenient to think through the prism of a domesticatory system, as it allows accounting for organic changes, multi-species relationships, and the diversity of hybrid communities; but it also achieves a broader biotechnical reconfiguration. Thus, the domestication process should not be seen only as biological transformations (genetic or behavioral) experienced by certain species. Rather, they are the emergence of systems of relationships, led by certain species and by humans, but which transcend them and include even environments. With this, we advance a reflection on fish farms from the re-appropriations of domestication in contemporary anthropology, underlining the role of techniques in the emergence of new forms of life, including human ones.

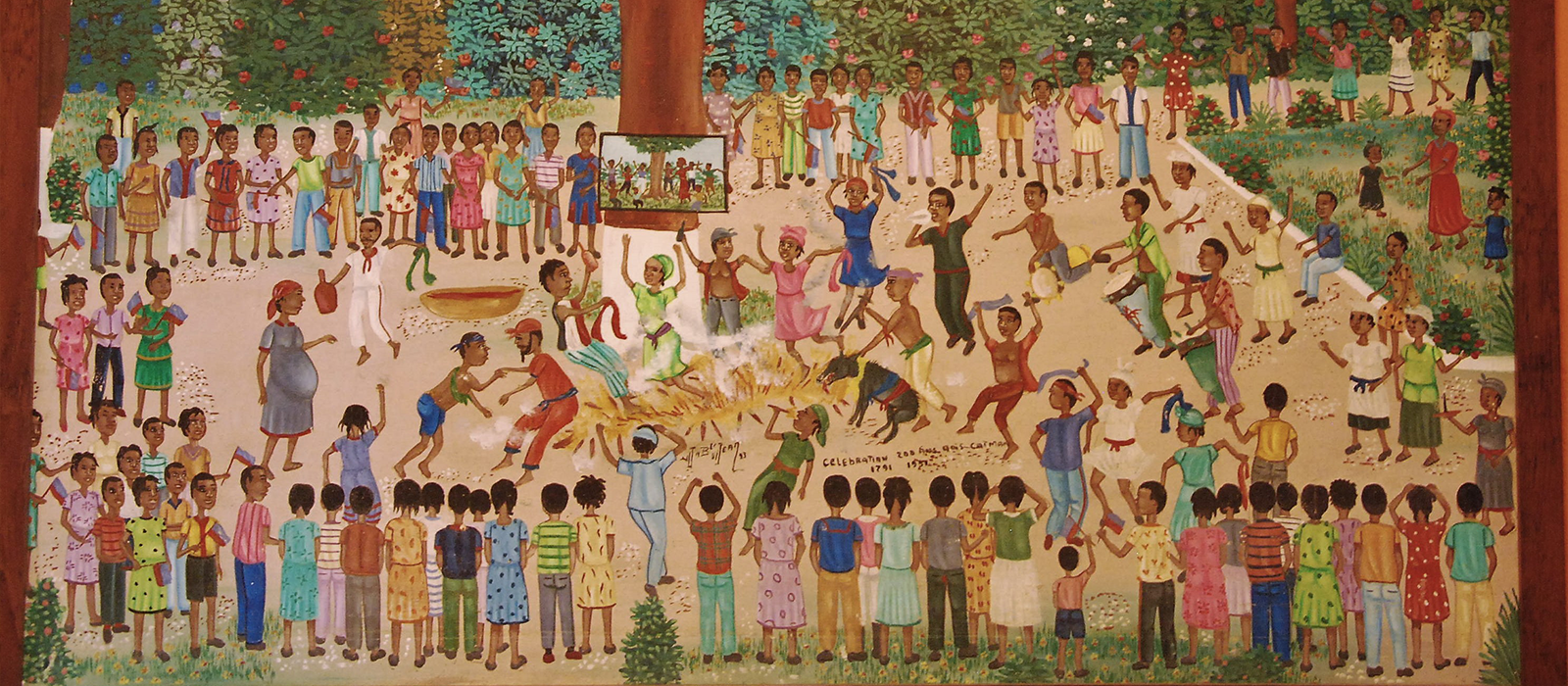

Genesis and death of a “domesticatory” system: pigs and the Haitian agrarian landscapes

Since Alfred Crosby's pioneering work, colonial historiography has increasingly focused on the place of animals in the landscapes of the Americas and the Caribbean. Chroniclers and colonial travelers described with an ambiguous fascination the native fauna and flora and their interactions with indigenous people while recording the arrival of European animals and their place in the consolidation of a plantation economy. Described by Jean-Pierre Digard as "an unknown aspect of American history", in the first part of this presentation I use colonial sources to discuss domestication with special attention to the techniques and interactions that gave rise to new domesticatory systems on the American continent. If animal husbandry, particularly that of pigs, made possible the consolidation of plantation economy, this also ensured the genesis of life forms based on relative autonomy that, over time, inspired radical demands for freedom. In the second part of this text, I move forward in time to think about the death of a domesticatory system in a specific ethnographic context: northern Haiti. Between the late 1970s and the early 1980s, state officials and experts (of different nationalities) landed in the country to eliminate all pigs on the island in order to create a health barrier to stem the advance of African swine fever. Known as Creole pigs, their death is conceived by many of my interlocutors as the 'end of life'. Thinking about the methodological dimensions that guide this seminar, my proposal is to recover an anthropology of techniques that targets the history of the arrival of animals in the New World, reflecting on the anthropological implications of thinking about history through ethnography, paying attention, in this case, to something that is no longer there, but that has left important marks in technical landscapes, ways of life and forms of conceiving the future.

Reencountering the Little Prince: affect as a contra-domesticatory technology

Despite the suggestion in the Spanish version of The Little Prince (Saint-Exupéry 1943), the fox never asked to be ‘domesticated’. What the fox asks is to be ‘tamed’ (in the French original: apprivoisée). That way, both the fox and the Little Prince could become reciprocally ‘unique’, and thus ‘creating ties’ (creer des liens) that would involve a negotiated friendship, and never subjugation. In this essay I suggest that Spanish translators inattention, who confound ‘domestication’ with ‘taming’, is also an issue with the anthropology of the other-than-human. With a few exceptions, coming notably from French scholarship (Digard 1988; Descola 2005; Despret 2004; Erikson 1987), multispecies ethnography has pivoted between analysis of domestication and theorizations of the wild. And hence we remain alien to the fox’s proposal, namely the possibility of establishing relations with the nonhuman based on uniqueness, affect, and reversibility.

This essay revisits the fox’s proposal through an ethnography of the relations that humans establish with two mammals who, like the fox, are highly intelligent: the pink Amazonian dolphins (Inia geoffrensis) and the European wild boar (Sus scrofa). The varied corporeal interactions between persons and these mammals exceed the biological and ethological attributes of wild and domesticated species. In relation to persons, both dolphins and wild boar individuals show reversible affects (that announce the potential for violence that ensues the lack of care in the everyday gestures of attachment). I suggest thinking interspecies affect as a contra-domesticatory technology, that is a practical and corporeal orientation towards the other - which invites cooperation while at the same time enables detachment and the restitution of independence for those organisms that become disenchanted with one another.

* All activities will be public and free. Links will be made available in advance.

** Work sessions in Portuguese and Spanish.